ANG KIUKOK: The Cynic, the Idealist

By Arlene Ang

Ang Kiukok is undoubtably one of the most prominent painters in contemporary Philippine art. He was born in 1931 in Davao City , the only son of Chinese immigrants, in a brood of five daughters. He studied Fine Arts at the University of Sto. Tomas from 1952-54.In 1965 he travelled to New York with the late Vicente Manansala, who was both mentor and friend. This proved to be a turning point in the development of his career as an artist. Culture-shocked by the stark alienation and dehumanisation he found in the American lifestyle, Kiukok began filling his canvases with distorted, robotic men reminiscent of Francis Bacon's. The change, however, caused the public to turn their interests elsewhere. Strongly marked by disillusionment and uncanny inner vision, these paintings were to be shunned for years to come.

In time, however, as he persisted in developing an expressionist style, appreciation slowly developed within the Filipino public. Since then he has enjoyed eminent success in and around Asia, with exhibits in Manila, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, as well as in the Netherlands, Canada and the United States. His works have also been recently selected for auction at Southeby's and Christie's.

Ang Kiukok's success stems mainly from the honesty of his art. Safe, soothingly-pretty subjects are not his cup of tea. He knows life isn't a bed of roses...at least, not roses without thorns. He doesn't try to deceive buyers and collectors with cheap publicity stunts or insist that a wallpaper motif is art nouveau. Though, of course, some buyers do look for such. One particular "collector" insisted that Mr. Ang paint him a large blue sailboat to match his blue bedroom.

It is one of Ang Kiukok's strengths that he never allowed himself to be bulldozed by the public's whims, even at the risk of remaining unrecognised and unpatronised throughout his lifetime--a risk he forced himself to accept as a matter of course right from the start. He does not waste time and paint dwelling on the native festivals so stereotypical of Philippine art. Nor does he paint flowery scenes and feathery ballerinas. Almost every painting seems twisted with outrage or internal suffering, giving voice to the Lowellian theme, "I hear my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell, as if my hand were at its throat... I myself am hell...."

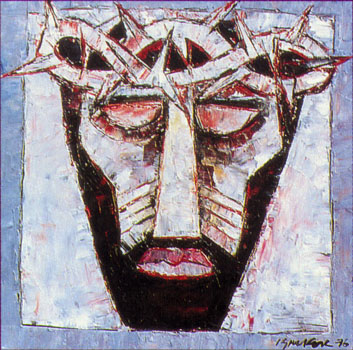

In a third-world country where religion, in Marxist terms, is opium for the people, even his depiction of Christ's crucifixion does not seem to suggest salvation. Impaled with thorn-like nails usually set against a backdrop of convoluted junk, his Christs may be dead but they are still very much in agony. "Yes, he died on the cross for us. But look around you--everything goes on as if nothing has happened. He died in vain, people don't really give a damn." Even his "Pietas" are shrouded in a darkness where Mother Mary grieves alone over her son's dead body in a wasteland of piled refuse.

Screaming figures bespeak both outrage and agony, but suffering does not liberate man from his fate. By contrast, the screams depicted in "Man on Fire" literally warn against playing with matches. But realisation has come too late for these burning figures.Dogfights and cockfights depict man's inhumanity to man. Soldiers are reared and trained like cattle to fight wars that heads of state launch at a whim.

Recently Ang Kiukok's paintings seem to have mellowed to less violent subjects such as harmless-looking clowns. Contorting themselves comically or juggling balls for the delight of their audience, they seem at first much more benign than his earlier works. But the joke is on the viewer, because it is he who is being both observed and aped. The clowns grin sarcastically or are bowed in mute despair. The richly-clad harlequin with vacant smiling eyes, the bashful joker, the vacuous deep-thinker make up just another part of the sorry cast strutting the world's stage.

More tender subjects project a different image of the artist: sensitive, passionate, nurturing. His "Mother and Child" images exude an inexpressible love, and the more rarely seen "Lovers" are entwined in a trance-like union, stripped of individual identity. A more detached Kiukok is revealed in his still lifes. An empty bottle or cabinet suggests a void of existential agony. The objects' seeming complacency about themselves mocks the viewer, "Are you so free and well-off, after all?"

Kiukok's paintings serve as reminders to a society where integrity and moral rectitude receive more lip service than practice. His art hopes to awaken and perhaps alter the deluded priorities of a world where the basic drive is toward the acquisition of wealth and the deception of one's fellow man.Ang Kiukok continues to be a respected but enigmatic figure in the Manila art scene, someone who does not suffer fools willingly, demanding honesty and straightforwardness from everyone he encounters--an increasingly tall order in these times. For many he seems the epitome of cynicism. And yet, when one looks at his art carefully, one sees he is a cynic only because he is, primarily, an idealist.

(Arlene Ang <[email protected]> was born in Manila of Chinese parents. She writes poetry, short stories, articles and translations. Her work has been published in LiNQ (AUS), RE:AL, Black Bear Review and is forthcoming in Oyster Boy Review, American Tanka and Dandelion (CAN).)