|

GOWANUS Spring 2002 |

||||||

| El

Señor de Qoyllur Rit段

By Adrian Locke

|

||||||

| This

Issue

Back Issues Click on image for full view Click on image for full view |

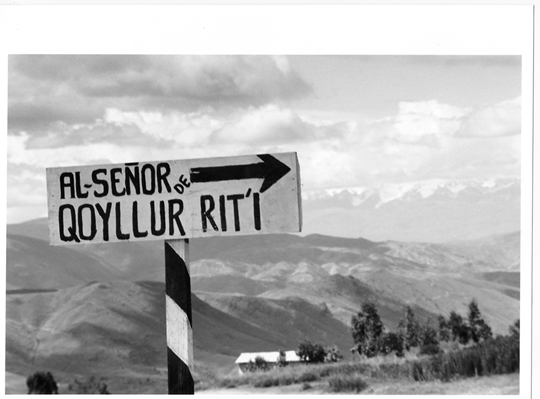

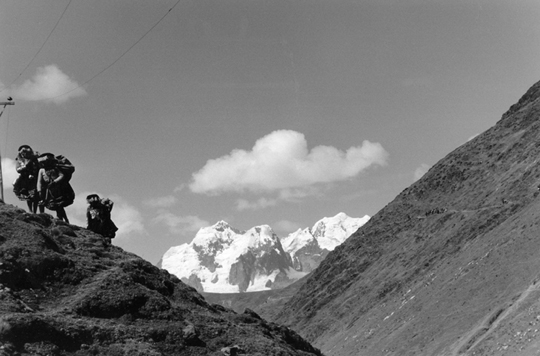

Located in

the remote valley of Sinakara, some 60 kilometres east of Cusco El Señor

de Qoyllur Rit段 [Lord of the Snow Star] is the most significant rural

pilgrimage shrine in Peru, drawing increasing numbers of people from all

over the country. Such popularity reflects the ability of Qoyllur Rit'i,

an image of the crucified Christ painted on a rock, to appeal to disparate

social groups. However, it is the native Andean character of Qoyllur Rit段

that continues to attract attention. The pilgrimage reflects the complex

marriage between native Andean religious belief and European Catholicism,

a process begun in the aftermath of the Spanish invasion of 1532, which

can be seen to meet at Sinakara demonstrating the manner in which Christian

religion has been accepted within the demands of an Andean social structure

and landscape. As a paradigm Qoyllur Rit'i proves that native Andean religious

belief and Catholicism can function alongside one another in a mutually

beneficial way. In essence, Qoyllur Rit'i reveals the crossover that took

place between both forms of worship in colonial Peru, and which led to

the emergence of a new syncretic religious belief system that survives

to this day.

The shrine of El Señor de Qoyllur Rit'i has its origins in a series of events that are believed to have taken place either in June 1780 or 1783 which, significantly, places it at the beginning or end of the failed up-rising of the native Andean revolutionary leader Túpac Amaru II (1780-1782). After the initial sequence of recorded events little mention is made until the mythical history of the miraculous events were officially recorded by a local parish priest between 1928 to 1946. Certainly, by 1931 the shrine was sufficiently popular to attract the attention of the celebrated Peruvian photographer Martín Chambi (1891-1973) who recorded scenes of the pilgrimage that year. The date of the initial miracle in the month of June, and subsequent pilgrimage, coincide with Corpus Christi, the principal religious procession of Cusco, during a grand parade of all the saints of the diocese centred around the cathedral. Today Qoyllur Rit'i is accepted as part of those celebrations since people participate in the pilgrimage before returning to Cusco in order to partake in the festivities there. The timing of the miracle clearly links Qoyllur Rit段 to the agricultural and pastoral calendar emphasizing its rural importance. Qoyllur Rit'i is like an onion with a number of different layers, as each is peeled away, another aspect of the whole is revealed. A clear example of a pilgrimage shrine that maintains a strong native Andean identity, Qoyllur Rit段 has changed over time and continues to evolve in response to the demands of a modern audience. Yet these changes do not detract from its perceived aims based around the needs of the local population who brought the shrine into existence. It is important to realise that Sinakara was a sacred place before the miracle happened, and that the miracle was a means to legitimise a local native Andean sacred site in the eyes of the Catholic Church. It is a classic example whereby miraculous icons are used as a means of inclusion through which native populations respond to the demands of a new, in this instance colonial, society. In the broad sense there are four separate

issues that can be defined here in respect to Qoyllur Rit'i. Firstly, the

miracle occurred at a time of extreme political disquiet, which divided

the immediate region into those groups in favour of, and those opposed

to, Túpac Amaru II. Secondly, the miracle safeguarded the religiosity

of Sinakara for the benefit of the local native Andean population, an aspect

that can be seen through modern accounts of the pilgrimage, and the continuing

observance of customs and rituals associated with it that define local

territory and identity. Thirdly, the occurrence of the miracle to a young

native Andean shepherd defines a need among the greater native Andean population

to demonstrate their ability to receive Christianity and to prove their

capacity for salvation. This statement of intent can be seen as the native

Andean population demanding, or being granted, the right to secure their

own variation of Catholic worship furthering the process of proselytism.

Finally, the events surrounding the establishment of El Señor de

Qoyllur Rit段 highlight the systematic transfer of the religiosity of the

pagan landscape in the creation of a new sacred topography. Such a process

has been traced to pre-Christian Roman Europe, through Medieval Spain to

the Americas.

|

|||||

Top |

||||||