WHITE LIKE ME

By Anthony Milne

It's time an outspoken local-white writer with the stature of an Anil Mahabir or LeRoy Clarke spoke up for us whites, French creoles and those of mixed ancestry and the contribution we have made to Trinidad and Tobago. We too should have an "arrival day" commemorating, say, the Spanish Cedula of 1783 which allowed us to receive the lands grants which inaugurated the development of sleepy Spanish Trinidad.If none of us had come to Trinidad--wherever we came from and however we came--the island (and the world) would be quite a different place. There would be no West Indies cricket, no Carnival, no calypso, no steelband, no tullum or roti. No Daaga or Dr Williams, no Cipriani or de Verteuil, no Naipaul or Capildeo, no Butler or Albert Gomes--and no Wendy Fitzwilliam as Miss Universe! (Why is there nothing named after Gomes, a local white of Portuguese descent who championed the rights of calypsonians and Baptists?)

I hope everything prime minister Basdeo Panday has said about equal treatment for all under the new Equal Opportunity Bill will apply to me and other local whites, as well as to people of mixed ancestry, Chinese, Portuguese, Syrians, Lebanese--and Arima's Caribs too. Together, Trinidadians who are neither African nor Indian make up at least 20 percent of Trinidad and Tobago's population.

On my national identity card I'm listed as white (part of 0.6 percent of the population), while close relations, as fair or fairer than me, are listed as "brown" or "light brown" (they are part of the 20 percent). How many of us are there, really?

This new bill can't be just for Africans and Indians. The Prime Minister made this clear when he laid the bill in the House on March 13th by quoting the national anthem. "Here every creed and race find an equal place" is a petition and pledge twice stated in the anthem, he said. "That pledge will be forever foremost among our national objectives."

With the sea change in public affairs that has occurred in the last two and a half years since an Indian-dominated government took over, we've begun to hear increasingly loud complaints from Indo-Trinidadians about black racism during the forty-odd years beginning just before independence in 1962. This was also a concern expressed during the Malborough House conference in London that originally gave us that independence. And it's not just Indians who worry. The rest of us have often felt the same way but haven't dared to speak out.

One of my relatives, of Portuguese descent, remarked: "It's not our money they want, it's our souls." He meant that the then black ruling class wanted to undermine the self-confidence of local whites.

I don't mean to suggest that local whites are all saints. I am sorry to say there are some who express racist views, just as do African- and Indian-Trinidadians. (I say "local white" and not "French creole", though the two terms have in some people's minds become synonymous and wide-ranging. Probably most local whites are French creole or have some link to them. And some French creoles, whether they like it or not, have a drop of the Congo in their Seine.)

Dr Anthony Maingot, a Trinidad French creole and social scientist, in 1962 confronted the attitude held here toward French creoles. He quoted Chief Justice HOB Wooding, who contributed an article on the "Constitutional History of Trinidad and Tobago" to the Caribbean Quarterly of May, 1960. Wooding described creoles as a "French land-owning aristocracy [who] remained a dominant minority exercising an influence far beyond its wealth and numerical strength...for nearly a century and a half until it became submerged, suddenly but remorselessly, beneath the onrush of political advancement during the last 30 years".

Maingot responded: "If, as is generally held today in the island, the French creole shared with the English expatriate 'the white man's burden' and partook in the ideology behind that imperialistic attitude, then one should expect to find among the French creoles some definite feelings as regards the disintegration of that 'white world'. That attitude should be one of either relief or regret. Or perhaps there is no feeling one way or the other but rather something close to amazement that they, the French creoles, now find themselves debited or credited with power and influence they never really enjoyed, except, perhaps, in a most indirect and superficial way."

He added: "It is difficult to state whether the view held of the French creole in Trinidad's society today is a result of causal factors other than psychological projections on the part of the mass or, even more important, on the part of the `new class' of creole politicians and intellectuals."

We must decide if we're going to be just selectively racist or not racist at all.

Just a fortnight ago I was told by a black Trinidadian that to his mind a French creole was a person of light brown complexion. This misunderstanding on his part must be due to the colloquial use of the term "creole" which some Trinidadians still use to refer to blacks, a holdover from the time when a distinction was made between black slaves born in the West Indies ("creoles") and those straight out of Africa. In the same way, servants (now referred to with political correctness as "maids" or "helpers") are still sometimes called "domestics", distinguishing them from slaves who worked the land. A "local white", in my black friend's eyes, was someone who looked like myself. I was surprised by his definitions, but shouldn't have been. Black Trinidadians traditionally know so little about their white brethren.

This lack of historical knowledge has been confused further by the presence in Trinidad of thousands of black Grenadian, Vincentian and Tobagonian immigrants, first or second generation, who know even less than do native blacks about white Trinidadians or the history and people of their adopted country. Indians are a bit more knowledgeable because they arrived here a number of generations before Grenadians and Vincentians. Of course there are blacks too who came long before the influx of Grenadians and Vincentians. But in the eyes of some blacks, local whites are indistinguishable from white American tourists. I find it annoying to be viewed by some of my own countrymen as an American tourist. Ironically, these "new blacks" assume or have been told that they and their culture--especially in Laventille, the East-West Corridor or Point Fortin--form the essence of what it is to be Trinidadian, though Trinidadians of many kinds with their own different cultures were here long before them.

Class is another issue. At the extreme ends of the scale, how could a landless black Grenadian peasant or craftsman living in Beetham Estate, Morvant, or on the burnt slopes of the Northern Range know anything about wealthy (and not so wealthy) French creoles with aristocratic pretensions living in Goodwood Park, other residential areas near Port of Spain, or in declining baronial splendour on estates in Icacos or Grand Couva?

Meanwhile true-true French creoles today can tell almost at a glance, or by innuendoes in brief answers to the briefest of questions, who belong to them and who do not, especially since they are mostly related to each other. By the same measure, they know who is not French creole, and this can apply even to other local whites.

So, many generations after the first French creoles came here in the late 1700s, some of them neither know nor care about their origins except in a superficial way. What they do know is the overwhelming influence and importance of the Roman Catholic faith in their lives, something they all share, which provides an ineradicable link with many other Trinidadians, black, brown or Indian. Put as simply as possible (since, as in all things, there are exceptions), French creoles are mostly descendants of French settlers who began coming to Trinidad after the Cedula de Repoblacion (Decree of Repopulation) was published by the Spanish in 1776, allowing non-Spanish Catholics to settle in Spanish territories anywhere in the New World.

An indefatigably enterprising man called Philippe Roume de Saint-Laurent, of French descent, resident (ironically) in Grenada, made the eighty-mile crossing to Trinidad to see what the prospects were like. He came with two other men, Dert and de Lapeyrouse. They were all much impressed by what they found. The white Spanish settlers and mestizos had never developed Trinidad on a grand scale--not on the scale, say, that British settlers or absentee landowners had worked the land of Barbados or Jamaica. French settlers began arriving immediately after the Cedula of 1776, from Grenada and other islands. Saint-Laurent, Dominique Dert, Picot de Lapeyrouse and Etienne Noel all bought land or received grants.

On November 24, 1783 (French creole Arrival Day?) the Spanish promulgated a Real Cedula para la Poblacion y Comercio de la Isla de Trinidad de Barlovento ("Royal Decree for the Population and Commerce of the Island of Trinidad"; "barlovento" simply meant "windward"). This second Cedula dealt specifically with Trinidad, and French settlers began coming here with their slaves in much greater numbers after 1783. They came with French-speaking free blacks and mulattos who held their own slaves. Grants of land were based on the size of families and the number of slaves they owned, though free black and coloured landowners, no matter how many slaves they owned, were only allowed half the land that whites were. That, essentially, was how the first French creoles--the first local whites, except for a few Spaniards--settled in Trinidad. Others came later: soldiers in the British forces that captured Trinidad in 1797 and republicans fleeing from royalist French forces.

Some of the old family names eventually died and new ones were introduced. Some are still familiar today: de Gannes, de la Bastide, Beaubrun, Le Gendre, de Gourville, de la Foret, de Boissiere, Peschier, Cazabon, Rochard, Vincent, Cipriani, Bernard and Borde. Irish, Germans and a few English came too and, like some of the Spanish, married into the French families, which is why today some true-true French creoles don't have French names. After the English took over, Scots and English came too, not to mention Portuguese, Syrians, Lebanese and Chinese.

Any equal-opportunity legislation must apply to the descendants of these people--at least twenty percent of Trinidad and Tobago's population--and as Trinidadian as anybody else.

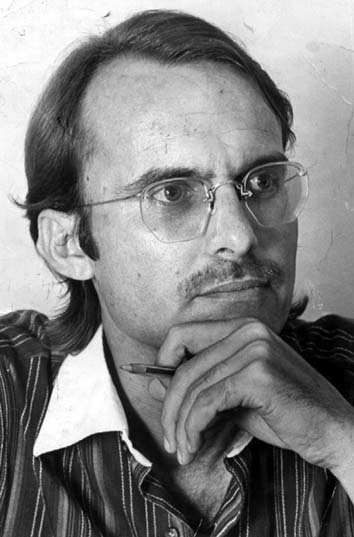

(Anthony Milne <[email protected]>, was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1951, educated there at St Mary's College, and subsequently in Canada and at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. He has worked as a journalist with Trinidad Express newspapers since July 1981, covering politics, parliament and just about everything else under the sun.)